By Jamie Andrus, Assistant Director of Student Well-Being

Not all inclusion is equal. If a wheelchair user wanted to enter the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History before 2021, they would need to leave the National Mall and head for Constitution Avenue to enter through the back of the building. Technically, the museum was accessible, but it would be difficult to claim that visitors with disabilities received the same grand welcome that non-disabled visitors experienced when climbing the monumental staircase to the columned South Mall entrance. That changed in 2021, when the museum constructed sloped walkways on either side of the main staircase. At the ribbon-cutting ceremony, Bill Botten, Training Coordinator for the U.S. Access Board, commended the new accessible routes, stating they allowed “easier and more dignified access to the museum for people with disabilities, older adults, stroller users, and others.” This is the difference between an inclusion that says, “you may enter” and an inclusion that says, “you are welcome here.”

No one wants to be an afterthought, and in architecture, Universal Design ensures that environments are accessible to all people without needing modification. The same principles can be applied to inclusive instruction through the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Framework and Guidelines. With Eastside Prep’s commitment that all learners feel a sense of belonging in the classroom, it’s no surprise that faculty are engaging in professional learning about UDL and integrating UDL strategies into the classroom.

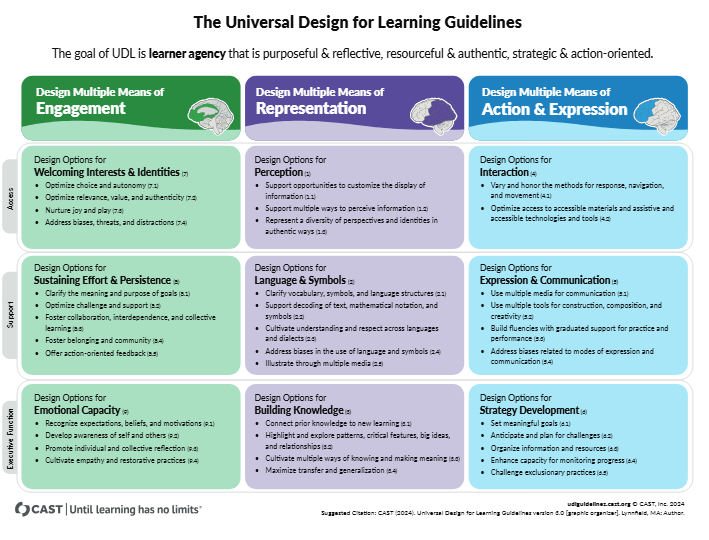

The UDL Framework and Guidelines were developed by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), a nonprofit in education research and development, to reduce barriers to learning for students with disabilities. As we see whenever we look to improve education for one group of students, CAST quickly realized that strategies that support differentiation and individualization of instruction are good not just for those with disabilities, but for all learners. One of my favorite things about working at EPS is that we recognize that every student brings a unique set of strengths, challenges, interests, and preferences into the classroom and that there is no single right way to learn, behave, or think. Supporting up to eighteen students in a classroom can become a daunting task if the teacher is responsible for adapting the curriculum for each learner. The beauty of UDL is that the focus is on designing a singular inclusive learning environment with the goal of helping students develop the agency to make choices about how they learn and demonstrate their knowledge.

UDL guides educators to support diversity in the classroom through providing multiple ways of addressing the “why” of learning (Engagement), the “what” of learning (Representation), and the “how” of learning (Action & Expression). The most recent iteration of the UDL Guidelines, published in 2024, also explicitly addresses the “who” of learning, recognizing that student identity is an essential factor in learner variability. The flexibility offered provides more support than traditional accommodations can. For example, allowing students to choose an audio version rather than a text copy benefits both a dyslexic reader and a student who commutes an hour each way to soccer practice and gets carsick if they read. Allowing students to choose their specific topic can provide more challenge for advanced learners and offer opportunities for students to see their identities reflected in their learning. At the same time, it caters to the interest-driven nervous systems of students with ADHD. This flexibility also more accurately reflects the autonomy we have outside of school.

While my ability to read words on the page is solid, audiobooks improve my focus. It also means I can listen in the car or while doing chores, since my first job (being a partner, mom, and stepmom while being a person with my own goals and pursuits) doesn’t allow much time for reading. When audio is offered as an option, I feel that my challenges with making time for reading are legitimate and that my participation is still valued. Similarly, students whose identities, abilities, and interests are considered in a lesson’s initial design know that their learning strategies are valid and appreciated. Again, it’s the difference between accessibility and belonging.

While the “why” of implementing UDL is clear, the “what” and the “how” require learning and practice. EPS faculty participate in a number of Program Development Days throughout the school year and can apply for funding to attend conferences or workshops. However, as informative as these intensive sessions can be, it’s much easier to apply new learning when you can engage with a topic over a period of time with the support of invested colleagues.

EPS can create classrooms that not only say “you may enter,” but also “you belong here.”

Recognizing the desire for professional learning that would directly impact the student experience, Karen Mills (Literary Thinking Faculty and Faculty Development Coordinator) and I piloted the EPStudy Groups program last school year. We ran two groups of around eight faculty members who committed to completing a training and meeting once a month to discuss incorporating the information into their work. Each focused on an aspect of increasing belonging for all learners: one group completed The Inside of Autism training by Kieran Rose, and the other worked through Katie Novak’s UDL Now! A Teacher’s Guide to Applying Universal Design for Learning. Mills, who led the UDL-focused group, says, “I loved learning about UDL with our study group this year. The method focuses on designing curriculum with all learners in mind, which is idealistic and intimidating but, we all learned, manageable when taken in small steps. The UDL mantra of ‘firm goals, flexible means’ is foundational and easy to remember, and it can be interpreted in many ways—it’s flexible, if you will.” With the participants now equipped with this mantra as well as practical tools for implementing UDL, EPS now has a cohort of faculty members who can support their colleagues in enhancing inclusion for their students. As we see with our students, collaborative learning increases motivation, accountability, and comprehension. Teachers can support each other through challenges and benefit from the creativity of others. We are excited to launch a second UDL-focused study group during the 2025-2026 school year so that more teachers can engage in this learning, and we can build momentum for UDL adoption at EPS.

Mills’ characterization of UDL’s guidelines as “inspiring and intimidating” is a fitting description for most inclusion initiatives. Reframing inclusive education to mean options for all rather than accommodations for some is a monumental shift in thinking. However, we know that disability isn’t the only barrier to learning. A lack of belonging in the classroom, whether due to individual identity or systems-level obstacles, not only impacts a student’s well-being but also their learning outcomes and achievement. It is always intimidating to think about the impact that our choices as educators have on students, but it is also incredibly inspiring to know that our instructional practices have the potential to make students feel welcomed, appreciated, and understood. Through a commitment to continued learning, taking risks, and knowing our students, EPS can create classrooms that not only say “you may enter,” but also “you belong here.”