By Sarah Peeden, Middle School Head,

and Dr. John Stegeman, Upper School Head

Beginning in the 2023-2024 School Year, Eastside Prep faculty undertook a multiyear project to review,  align, and reimagine grading and assessment practices across grades five through twelve. Now entering its third year, teachers are beginning to implement changes derived from this work. Our project is not one that will rapidly upend this important component of the school experience for students. Instead, we are innovating wisely and cautiously, with an abundance of communication and care for students. This article marks the third installment of a multipart series in Inspire magazine, to keep our community informed and promote dialogue.

align, and reimagine grading and assessment practices across grades five through twelve. Now entering its third year, teachers are beginning to implement changes derived from this work. Our project is not one that will rapidly upend this important component of the school experience for students. Instead, we are innovating wisely and cautiously, with an abundance of communication and care for students. This article marks the third installment of a multipart series in Inspire magazine, to keep our community informed and promote dialogue.

FOUNDATIONAL CONCEPTS

Grading and assessment are central to American secondary school life, but they are rarely discussed beyond letters, numbers, and averages. Assessment is defined as a means of gathering data on performance. Sometimes this data is gathered before or during a unit of study to inform teaching practices; this type of assessment is known as formative assessment. Summative assessment, in comparison, occurs at the end of a unit of study. This form of assessment provides students with feedback about their learning and can also provide educators with insights into the impact of their teaching.

Grading is something different. It is a shorthand for communicating feedback collected through assessment (Marsh, 2023). Most Upper School systems for grading are based on one-hundred point (percentage) or four-point scales. In most instances, though, these systems are unreliable communicators because their inputs can vary greatly, from school to school or even teacher to teacher. For example, grades could be calculated on a curve, with a bell-like distribution; they could be averaged across a grading period; or they could be informed by a student meeting standards or expectations set by a rubric or contract.

When letters like A-F are involved, there can be even more confusion, as each letter can be associated with pluses and minuses and inconsistently paired with point values. In effect, grades can be interpreted in many ways, especially if there isn’t clarity about what, how, and why things are evaluated.

“We should measure what we value, or we’ll

end up valuing only what we measure.”

A BRIEF HISTORY OF GRADING PRACTICES IN THE UNITED STATES

In the United States, grading as we know it today with scales, percentages, and letters has its roots in 19th-century industrialism and the expansion of education beyond the home to the school. Before that time, feedback received by a pupil was often narrative in nature.

While numerical- and letter-based grading were originally products of American higher education, they were quickly adopted across the country as schooling moved from small, one-room multiage enterprises to larger and increasingly routinized, publicly funded operations in which efficiency was necessary to address increases in student loads (Guskey et al., 2024).

In these classrooms, grading was informed by then-cutting-edge practices adapted from business and social science. With mechanical influences like standardization, grades served to sort students and also provide opportunities for extrinsic motivation, often in ways that reinforced pre-established social constructs and problematic hierarchies related to gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

Grades now impact everything from car insurance rates for students to college admissions and hiring decisions for graduates (Guskey et al., 2024).

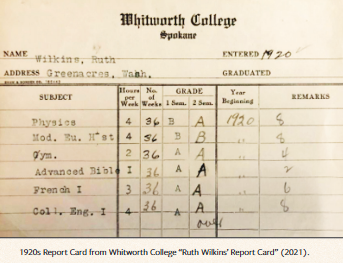

Although contemporary students’ uses for grades may have changed, the feedback they receive is largely the same as that of students from a century ago, as the 1920 sample on page twelve from Whitworth College shows. Interestingly, the greatest difference in report cards from then and now is the fact that compliance-based and comportment-oriented marks are not explicitly measured. Considering this lack of innovation and increasing anecdotal data suggesting that grades at EPS may have a negative mental health impact on students, it is no surprise that Eastside Preparatory School would undergo a thorough review of its grading practices to ensure that it was meeting the needs of its students and providing them with the cutting-edge educational experience that is so central to our Mission and Vision.

STUDENT FEEDBACK

Since the beginning of this project, we have explored the topic of grading and assessment and its connection to the EPS community in service to the school’s Strategic Priorities. This work has included conducting an in-depth analysis of internal grading practices, orchestrating professional development for faculty members about innovative approaches to assessment, developing a set of schoolwide competencies, and finally, gathering feedback from families and students.

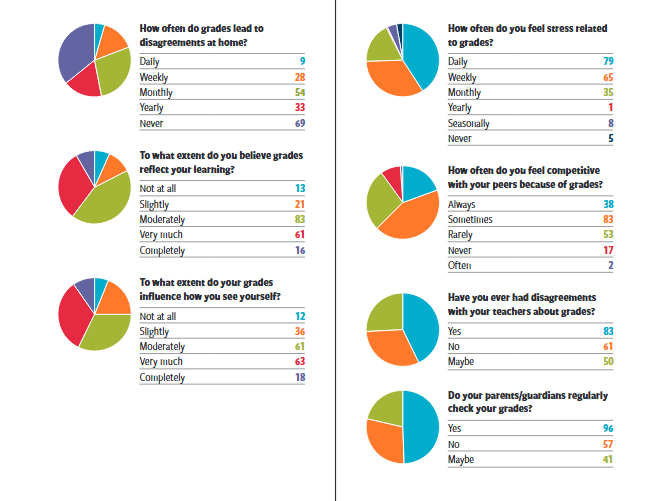

At each point in the process, we have provided the community with an update, most recently in the Spring 2025 issue of Inspire, which included key takeaways from our Listening Groups with parents and guardians. Since the release of that publication, we have surveyed and analyzed 194 anonymous responses that we received from students across fifth through twelfth grades. The responses we received paint a complex picture of the experiences of students at EPS, one that includes variations based on gender as well as distinction based on grade level and division.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

In both quantitative and qualitative responses to questions about their perceptions of grading, students overwhelmingly expressed concern about stress related to grading. The highest levels of stress were associated with ninth-grade students, though all grades presented daily stress.

Some of this might be expected. For instance, one eleventh-grade respondent asserted that “grades play a huge role in determining our future, particularly college acceptance.” Still others noted that the stress to perform at a certain level often meant focusing on achievement and not on growing. As one eighth-grade student opined, “[thinking about grades is] so stressful, it makes my work not about learning but meeting criteria on a rubric.”

In addition to academic pressures, many respondents shared about social pressures from friends and family associated with grades. As one sixth-grade respondent noted, “They [grades] make people judge you.” Another sixth-grade student shared that grades are important “because [the grade you get] determines what college you go to. If you go to a good college, good life, good money, good spouse. But a bad college means no money, bad life, bad spouse.”

DATA

If you could describe grades as an animal, what would they be and why?

{ “A snake, because they could be lurking anywhere (always there).” { “A termite, can be pointy and annoying but ultimately necessary for the ecosystem.”

{ “Mosquito—very annoying, sometimes dangerous, vital for life.”

{ “A human because it is way too complicated.”

{ “A well-behaved circus elephant—it’s always the elephant in the room, but unless something goes catastrophically wrong, there’s no need to talk about it.”

{ “A badger, because when they’re nice they look cute and are helpful, but when they’re not, you get mauled to death and don’t have a future anymore.”

{ “Grades are something similar to a goldfish. Goldfish are dependent on your care and nature and can die otherwise. Yet your ability to care for it might define you as a person. However, what’s most important to understand is that goldfish are limited to the fishbowl, they only can reflect and explore a small part of the vast bodies of water in the world. Your grades are only a goldfish, and you are a body of water. It can only define you to a certain extent, there is so much more beyond it to explore.”