By Alicia Hale, Middle School History Faculty

THE THEATRE IS DARK AND STUFFY. ON THE screen a protest about police brutality comes to a crescendo and I hear quiet sobbing behind me. I slowly crouch and walk to the back of the theatre, handing out tissues to students who are visibly upset by the events on the screen. The film does not shy away from the theme of the Black Lives Matter movement and the plotline continues to put emotional pressure on these students all the way through the final scene. As we all file out into the quiet lobby red-eyed and exhausted, blinking in the sunlit space, we are changed.

The seventh graders watched The Hate U Give this autumn, a movie based on the debut novel by Angie Thomas. It recounts the life of a young black girl who lives in a dangerous neighborhood but attends a magnet school that is predominantly wealthy and white. The main character has to struggle with code-switching on a daily basis and when she witnesses a fatal shooting, she is faced with the impossible choices between her two worlds. This book was transformative for many readers when it was first published in 2017; not only was it a young adult (YA) novel that was written by a black author, but it spoke directly about the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement on young people. The publishing world became more aware of the need for books that not only were written by but also feature protagonists who are people of color. The film does an excellent job bringing the book to life and it was a very meaningful experience for seventh graders during our Education Beyond the Classroom (EBC) day.

The seventh graders watched The Hate U Give this autumn, a movie based on the debut novel by Angie Thomas. It recounts the life of a young black girl who lives in a dangerous neighborhood but attends a magnet school that is predominantly wealthy and white. The main character has to struggle with code-switching on a daily basis and when she witnesses a fatal shooting, she is faced with the impossible choices between her two worlds. This book was transformative for many readers when it was first published in 2017; not only was it a young adult (YA) novel that was written by a black author, but it spoke directly about the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement on young people. The publishing world became more aware of the need for books that not only were written by but also feature protagonists who are people of color. The film does an excellent job bringing the book to life and it was a very meaningful experience for seventh graders during our Education Beyond the Classroom (EBC) day.

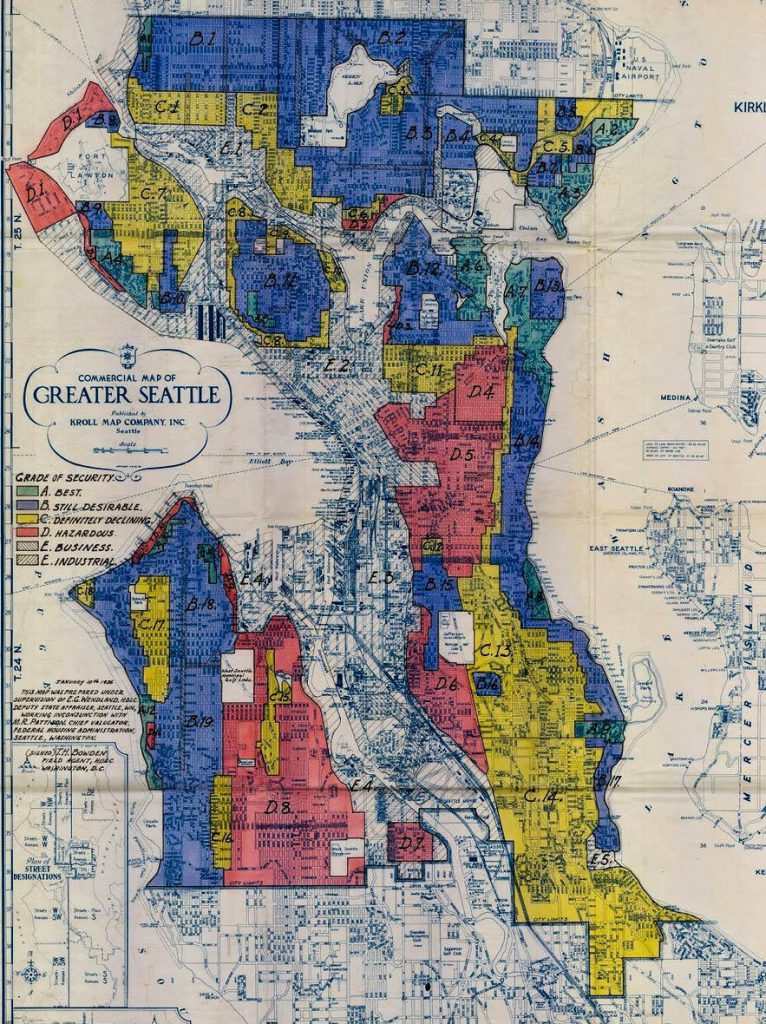

After the film, students came back to class with so many questions about the root of racial issues they saw that I put the WWII Homefront curriculum on hold and made space for their self-directed learning. Students asked why and how black neighborhoods were traditionally seen as poor and disadvantaged. We began to look at something called redlining that began during the New Deal:

It started with the Great Depression. Rampant foreclosures had left lenders fearful and so the federal government devised a solution. It would encourage banks to loan money to would-be home buyers by developing maps that would show where their mortgages were most likely, and least likely, to be paid in full. It was called “redlining” and the stated aim was economic development. The result was racial discrimination. -CrossCut media (part of KCTS )

This led us to understanding the racially restrictive covenants that existed here in the greater Seattle area; a racially restrictive covenant is when racial restrictions are written into the deeds of houses in some areas to prevent certain people from living in those neighborhoods. Students were interested when I showed them an area map with historically redlined neighborhoods (see Figure 1 on page 23). They understood how the neighborhoods

that we see today are part of the structure that was put in place by this map. When I gave them a list of the racially restrictive covenants from the UW Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project that were on the Eastside, students were suddenly faced with the reality that they live in areas where there were historic racial restrictions. It was a difficult moment in class, when students read the language that was used to make sure neighborhoods stayed white.

The Kirkland Heights covenant read: “Lot or lots shall not be sold, conveyed, or rented nor leased, in whole or in part, to any person not of the White race; nor shall any person not of the White race be permitted to occupy any portion of said lot or lots or of any building thereon, except a domestic servant actually employed by a White occupant of such building.”

This information was difficult to process, and one morning over breakfast with David Fierce I reflected on what I had been teaching. He was sympathetic to the complexity of what I was trying to teach the seventh graders and his insight was invaluable as I tried to find a way to make this lesson have deeper meaning for the students. I knew that the eleventh graders would be addressing the impacts of redlining later that year and I suggested we work on a more interactive version of a teach-in that we had done earlier in the year, when the eleventh graders had taught Middle School students about U.S. government. This time around, the seventh graders would lead the lesson by showing eleventh graders the places on the Eastside where there had traditionally been racial covenants in their neighborhood. We wanted to create something interactive so that students could work together to create meaning out of the data and give a chance for Middle School students to lead.

This information was difficult to process, and one morning over breakfast with David Fierce I reflected on what I had been teaching. He was sympathetic to the complexity of what I was trying to teach the seventh graders and his insight was invaluable as I tried to find a way to make this lesson have deeper meaning for the students. I knew that the eleventh graders would be addressing the impacts of redlining later that year and I suggested we work on a more interactive version of a teach-in that we had done earlier in the year, when the eleventh graders had taught Middle School students about U.S. government. This time around, the seventh graders would lead the lesson by showing eleventh graders the places on the Eastside where there had traditionally been racial covenants in their neighborhood. We wanted to create something interactive so that students could work together to create meaning out of the data and give a chance for Middle School students to lead.

We created a map that scaled King County correctly so that students could make sure to understand the full sense of how many spaces did not allow people of color to buy or reside in houses in their own present-day neighborhoods. Students would work in small groups to label stickers with the names of the neighborhoods listed in the UW archive document and place them on the map. On the day of the teach-in, over 100 students buzzed around us as the map was filled in with hundreds of colored stickers; some students could be heard reading the covenant language to each other, shocked at how derogatory some of the words were.

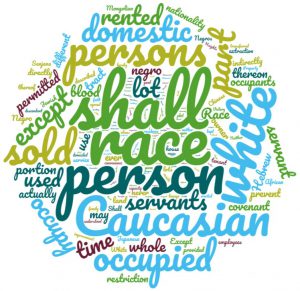

As part of the process, we had the groups collect the most shocking phrases they found as they generated their geographic section. We created a word map using the most repeated words in the collection and made them larger the more times they were repeated (see Figure 2 above). This is a way to help sum things up for students as they were not given the complete list of racially restrictive covenants in King County. The other part of this process was the “snowball fight,” which is a type of check-in that allows students to exchange ideas anonymously, and happens to involve having a good time in the process. Students wrote down the phrases they submitted to the word map on slips of paper and crumpled them up into a ball. We went outside and threw them at each other in a “snowball fight.” After two minutes of chaos we all grabbed a ball and opened it up. Students were asked to read the phrase to a partner and reflect in one word what it felt like to see all the ways that people of color had been restricted in King County.

All of a sudden, the space around us went quiet as they read—and around me rose a cloud of different words in a chorus of voices that craved a way to create change.

Creating a space for students to share this complicated history together allowed them to have supportive peer conversations about some of the hard history of our region and its ongoing impact. I was so impressed with the interactions between the eleventh and seventh graders that I plan to find a way to integrate this experience into my classes next year. Building and supporting each other’s learning through Upper School peer mentorship is such an amazing way to create deeper meaning for all the students at EPS.