Mr. Edmonds, Dr. Duffy, and Dr. Castro sent along selfies as they teach from their remote locations (including a field trip to Synergy Recording Studio by Mr. Edmonds).

Deciding to Lead

By Dr. Terry Macaluso, Head of School

FIRST IT WAS “CORONAVIRUS.” SOON IT BECAME COVID-19. THEN THERE were phrases like “social distancing.” I was a child in the 1950’s, growing up in a small suburb of Denver, Colorado. Neighborhoods were small enclaves where houses were mostly the same, families were mostly the same, and everyone was prospering in those days, following the end of the Second World War.

Moms mostly stayed home. Dads came home at 5:00PM. Dinner was at 6:00PM. Everyone was there. There was talk from the neighbors as well as my daily report from the business of first grade; my two younger siblings, one in a highchair, and one being cradled, were present. Tiny hands slapped the tray on the highchair. The occasional whimper escaped my baby brother’s mouth, and I learned that I was about to have the chicken pox.

The aim then was to consolidate exposure to contagious viruses by putting all the children in the neighborhood in proximity to whoever was already sick, and then to let the incubation pass while each of us—one right after the other—became sick as well. In this way the moms in the neighborhood would all be taking care of sick kids at the same time—so the entire wave of contagion would be concluded on their timeline. Measles, mumps, and chicken pox—all conquered within a two-month summer.

The aim then was to consolidate exposure to contagious viruses by putting all the children in the neighborhood in proximity to whoever was already sick, and then to let the incubation pass while each of us—one right after the other—became sick as well.

Now, sixty years later, I’m doing the opposite. Social distancing is the new normal.

I was reminded of this mid-twentieth century practice when, in late February, Kirkland became ground zero for COVID-19 in the United States. The message: get people away from one another—and keep them away. On February 28, I was communicating with our Senior Leadership Team about the possibility of transitioning to EPSRemote. We knew we needed to get everyone out of the classroom and off the campus; but we didn’t know how to determine the criteria that would signal that it was “okay to get back in the water.”

The discussion followed the same pattern through hours of conversation and email reasoning. Yes, we probably do need to get everyone off campus. But…how will we determine when to return? The preliminary answer was made clear for me when I realized that we could designate a potential return date. It was all tied to our EBC travel experience week, followed by spring break. We would conduct classes remotely until spring break had passed. That decision was made on March 1. At the end of the day on March 2, we gathered students in the theatre to tell them what we were going to do. They were asked to take everything home with them and to prepare to be away for six weeks.

I had to make a decision without knowing anything about what the consequences might be.

For the next several days, the email chains grew longer and louder. Independent school colleagues were trying to find support for their decisions to sit tight. How ridiculous to close a school. What a terrible, alarmist message to send to the community. On March 13, the governor mandated that all schools in the state close— regardless of their capacity to transition to virtual education.

For the next several days, the email chains grew longer and louder. Independent school colleagues were trying to find support for their decisions to sit tight. How ridiculous to close a school. What a terrible, alarmist message to send to the community. On March 13, the governor mandated that all schools in the state close— regardless of their capacity to transition to virtual education.

Apparently, I have since been reprieved, inasmuch as my team and I made the decision two weeks before the governor made the decision for everyone. But the reprieve means even less than the original charge; caring what other people think hampers one’s ability to act.

I’ve thought and written about leadership for a very long time, but I have to say that those last days of February, as they melted into the first days of March, I had to make a decision without knowing anything about what the consequences might be. As is often the case when people have to make decisions that impact other people, this was a moment in which the capacity to live with ambiguity—to not know—was a requirement. This is the reason there is no “I” in team. Without a team of trusted colleagues who work together every day, and have for over fifteen years, I’m not sure I’d have mustered the courage to be the first to make the decision to act in such a public and definitive way. I remember clearly: We were seated around a large boardroom table and someone said, “Let’s lead.” And so we did.

Implementing EPSRemote

By Dr. John Stegeman, Head of Upper School

WHEN PEOPLE ASK WHAT DREW ME TO Eastside Prep, I always talk about our spirit of adventure and drive to innovate. Our response to COVID-19 began as an adaptation to a global health crisis when it landed in our backyard, but we quickly realized that the transition to EPSRemote was going to require fresh thinking about teaching and learning in virtual space. Every member of the community dove in with enthusiasm to tackle some big and interesting challenges. While many of our solutions were built with technological tools, it was the willingness to innovate quickly and wisely that has really made EPSRemote a success.

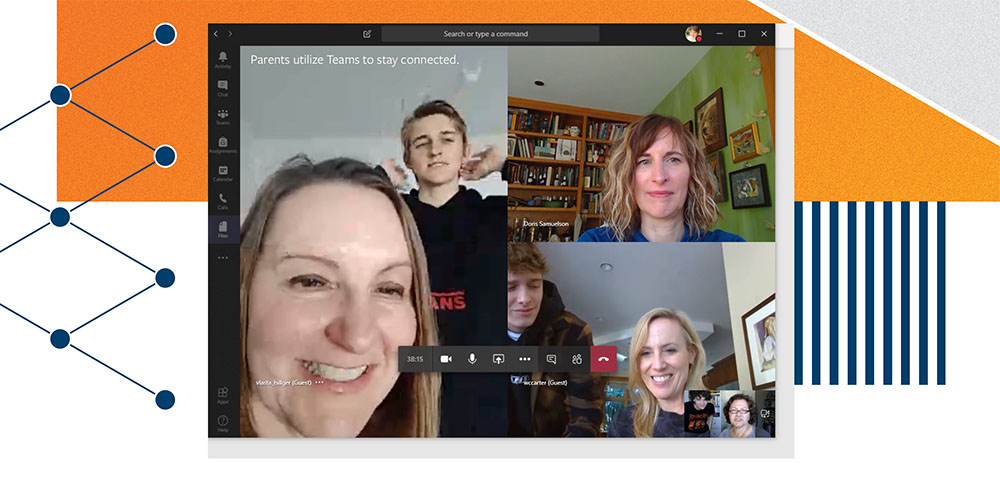

We started with several elements of first-rate technological infrastructure in place, which made the transition much faster and more effective than it otherwise would have been. Our one-to-one laptop program, with everyone on compatible devices and a shared suite of software, gave us a huge head start. Canvas is an excellent learning management system, and most of our course materials are housed in Microsoft OneNote, both of which are accessible to teachers and students remotely. But so much of what we do on campus is collaborative that sending people off into distant corners of the Seattle area to learn on their own felt anathema. We knew we needed a tool for collaboration, and we wanted to keep people interacting on a schedule that would bring regularity and predictability to the days and weeks ahead. Microsoft Teams gave us that capability.

Within one week of announcing the transition to EPSRemote, teachers and students closed out the Winter Trimester. Our technology team set up every class in the school to function in Teams and trained faculty to run real-time, synchronous classes. We conducted a three-class practice day, where teachers and students convened on Teams and established the conventions of online classes. As you might imagine, students quickly discovered advanced functions that superseded the basics we taught them. By the following week, students had learned to mute the audio of other participants (including the teacher’s) and modify their voices to sound like robots. Teachers learned that classroom management is a necessity in virtual space, too.

From the outset we were concerned about the amount of time students would spend on digital screens in this new format. We asked teachers to plan lessons that enabled interaction through Teams for about half of each block, and allowed students to leave the setting for the other half to complete assignments. This structure provided some balance to the learning experience and served as a good starting place, but ultimately we realized the need to continue refining our practice. Teachers reported that it was harder to gauge students’ understanding through Teams, and that expectations had to be meticulously communicated, which led to more preparation time and somewhat slower delivery of instruction. Some parents reported that students were finishing the days’ activities early, and with limited options for activities outside the home given the recommendations for “social distancing,” they were ending up in front of a television or computer screen during their free time, too.

Our technology team set up every class in the school to function in Teams and trained faculty to run real-time, synchronous classes. We conducted a three-class practice day, where teachers and students convened on Teams and established the conventions of online classes.

As the first week elapsed and announcements from state and federal officials indicated it may be longer than expected before we could return to campus, we began to consider ways that we might extend learning beyond the limited scope of our initial plans. “Homework,” reading, and skills practice outside the class period would need to return to more typical levels. When working at a distance, electronic delivery of assignments seems to be the most efficient mechanism, but that puts students in a position of remaining on screens for much of their day. We are currently working to find ways to plan more analog activities, incorporate movement, and get kids out of the confines of their work spaces during the day. Creative solutions to these challenges are emerging class by class, but there seem to be no straightforward path to the problem of “too much tech” when operating remotely.

That is why the spirit of our community is so important. A broad challenge like this requires everyone to pitch in. The EPS community has remained supportive of our efforts and one another. Critical thinking, responsible action, compassionate leadership and wise innovation remain our lodestars, and the kind, supportive interactions that characterize our days on campus have continued by email, chatroom, and teleconference. The intrepid spirit of this community will carry us through this challenge and whatever others the future brings.

Looking Ahead

By Sam Uzwack, Head of Middle School and Student Support Services

AFTER THE FIRST FEW DAYS OF EPSREMOTE, OUR community began to fall into new routines. And yet with each passing day, new challenges emerged. Organized sports were canceled across the region. Sounders games, music concerts, theatrical productions—all nixed. Then the school closures started in earnest, first with the Seattle metropolitan area and then extending to the whole of Washington state. On Sunday, March 15, the order came from Governor Jay Inslee that all restaurants and entertainment and recreational facilities would close. Finally, on March 25, the governor announced the “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order.

The experience of the first three weeks of online school was a gradual stripping away of the day-to-day, and perhaps more fundamentally, the status quo. Each day, with new restrictions, the fear of the coronavirus intensified and concern for one another grew. And, as is true with any emergency situation, everyone processes this in their own way.

For me, I’ve tried to sort out my own feelings about this emergency by attempting to look ahead to a day when this crisis will have passed, and we will be able to return to our “normal” daily lives. This is where I think we—as a society, as a school, and me, as a parent—have a lot of thinking to do, and have a true opportunity to re-examine what has become the norm. In recent years, the amount of anxiety and stress we, as a society, have chosen to place on our young people has grown tremendously. It did not happen overnight, but over a long period of time, slowly and gradually, until we arrived at the place we are today. Students’ schedules are packed tight, with no room for error, let alone time for a walk in the park, a nap, curling up with a good (nonrequired) book, or a night off with friends. Select sports, robotics competitions, academic enrichment, children’s symphonies, competitive chess, college-prep classes—separately, these are all wonderful and creative pursuits, but the aggregate of these commitments is leaving our children with precious little down time at best and impacting their health negatively at worst. The over-programming of our children also robs them of some of the very best learning that can occur, for it is during unstructured time when kids figure out how not to be bored, deal with ambiguity, and discover new interests.

We also need to take a good long look at our own adult habits. Perhaps the days of an entire region driving somewhere alone in our cars to do work, that could otherwise be done remotely, are over. Perhaps our unquenchable thirst to consume now and always over our smartphones will be tempered. Our own experience with online school might unlock new ways of thinking about time and space, allowing students and families to engage their education in here-to-unforeseen ways.

When this crisis fades into the history books…and it will, eventually…we will continue to make good on our EPS vision, of guiding students to create a better world. But we, the adults, first need to set them up for success, and perhaps now, we have the opportunity to create a better world for them moving forward. A world in which they can be kids again—be more creative and be more themselves.